I am from a generation where we reasonably feared, and secretly yearned for, an Earth-shattering, apocalyptic event. You can see this in the movies of our time (Mad Max, Escape From New York, Damnation Alley, Planet of the Apes, A Boy and His Dog, Logan’s Run, and The Omega Man, to name but a few). Out of that amazing genre, one of the most memorable post-apocalyptic fictions of my (I want to say childhood, but I was thirteen when this came out) formative years, was Thundarr the Barbarian. If you don’t know this Saturday morning cartoon, this is the amazing trailer. (It really is just the trailer).

What better apocalypse can there be than a runaway planet ripping the Earth and Moon asunder (I blame Pluto. After years of being bullied by the Earth, it decided to get back at us for ostracizing it from the rest of the Solar System). And two thousand years later, people have survived, but some have turned science into magic, how cool is that? Thundarr the Barbarian burned a place into my psyche and and my heart, and while it is incredibly cheesy when I watch an episode or two now, and the animation was cheap and stilted, it really fed my imagination.

So when I saw this book sitting on the shelf of my local thrift store…

…I had to have it. Was this the book that the cartoon was actually based on? Was it a novelization of the TV series? I wasn’t sure. The book was written ten years before the cartoon series premiered, so it likely came first, and TV Thundarr looked startlingly similar to book cover Thundar, so there was enough connection for me to spend the $2.95 to buy this book and check it out (Interestingly enough, the cover price of this 1971 publication was 75 cents-it had already almost quadrupled in price, a sound investment).

Fortunately, when I read this book, I had already developed a serious working knowledge of the books of Edgar Rice Burroughs, from Tarzan, and the Princess of Mars, to the Pellucidar Series, and the Time Forgot books. When you grow up needing dinosaurs in your life, Burroughs is a good place to start. Of course, now every kid has Michael Crichton and the Jurassic Park books and movies. Spoiled. Either way, the book Thundar: Man of Two Worlds, is what we would now call fan fiction, by author Stuart J. Byrne writing under the name John Bloodstone, melding many of the worlds and even the story-telling style of Burroughs together into this tome (I needed an alternate word for book, but 192 pages is a tiny tome).

It wasn’t a bad book, but it wasn’t John Carter tearing up Barsoom, either (and that Disney movie with Taylor Kitsch was way better than people gave it credit for). While Thundar: Man of Two Worlds had a princess and a primate-like sidekick, and scientists whose powers rivaled sorcerers, it didn’t have the breadth nor imagination of the Saturday morning cartoon. I’m glad I read it, and I couldn’t really tell you unequivocally that the cartoon was based on the book, but if it was, I would use the word inspired, at best.

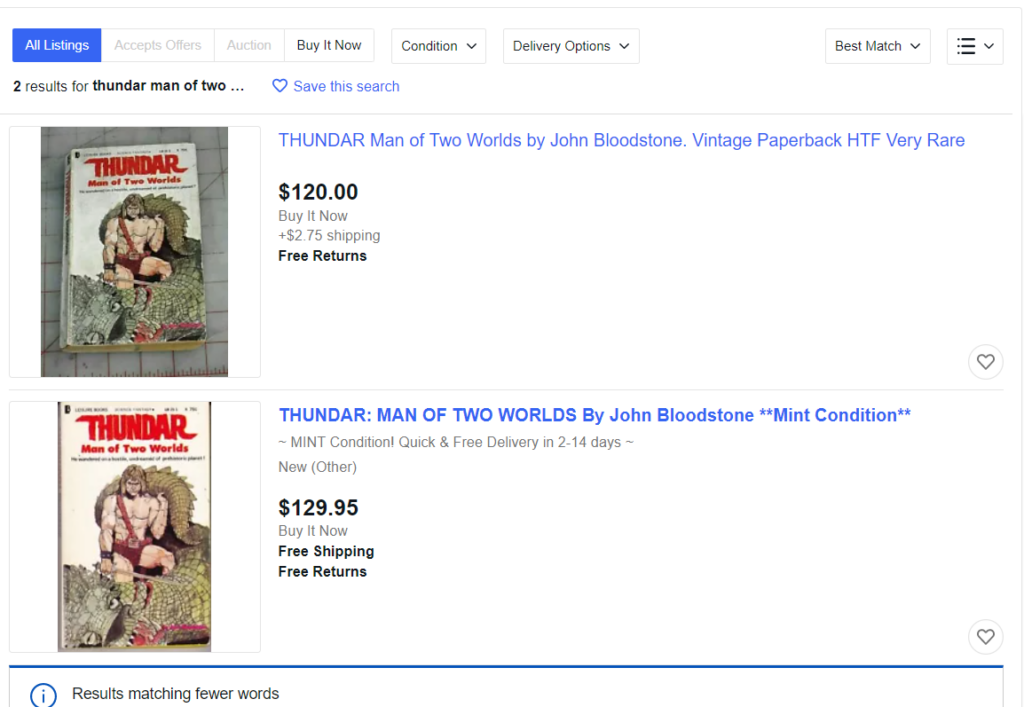

And as far as a sound investment, this is what I found on eBay.

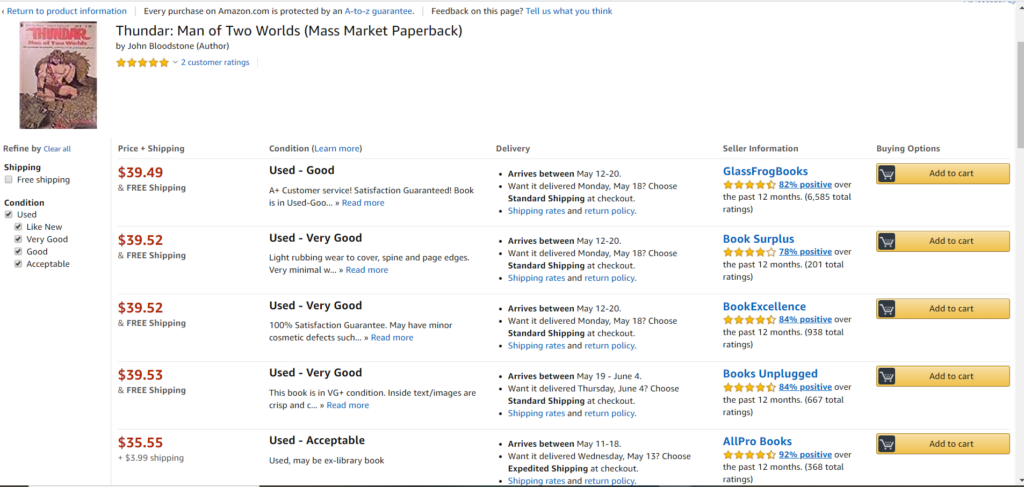

But this is what I found on Amazon.

Either way, I think I’m going to hold onto this sound investment.

See, I’m not the only one. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have to go watch a few Thundarr episodes, if I can find them on YouTube.